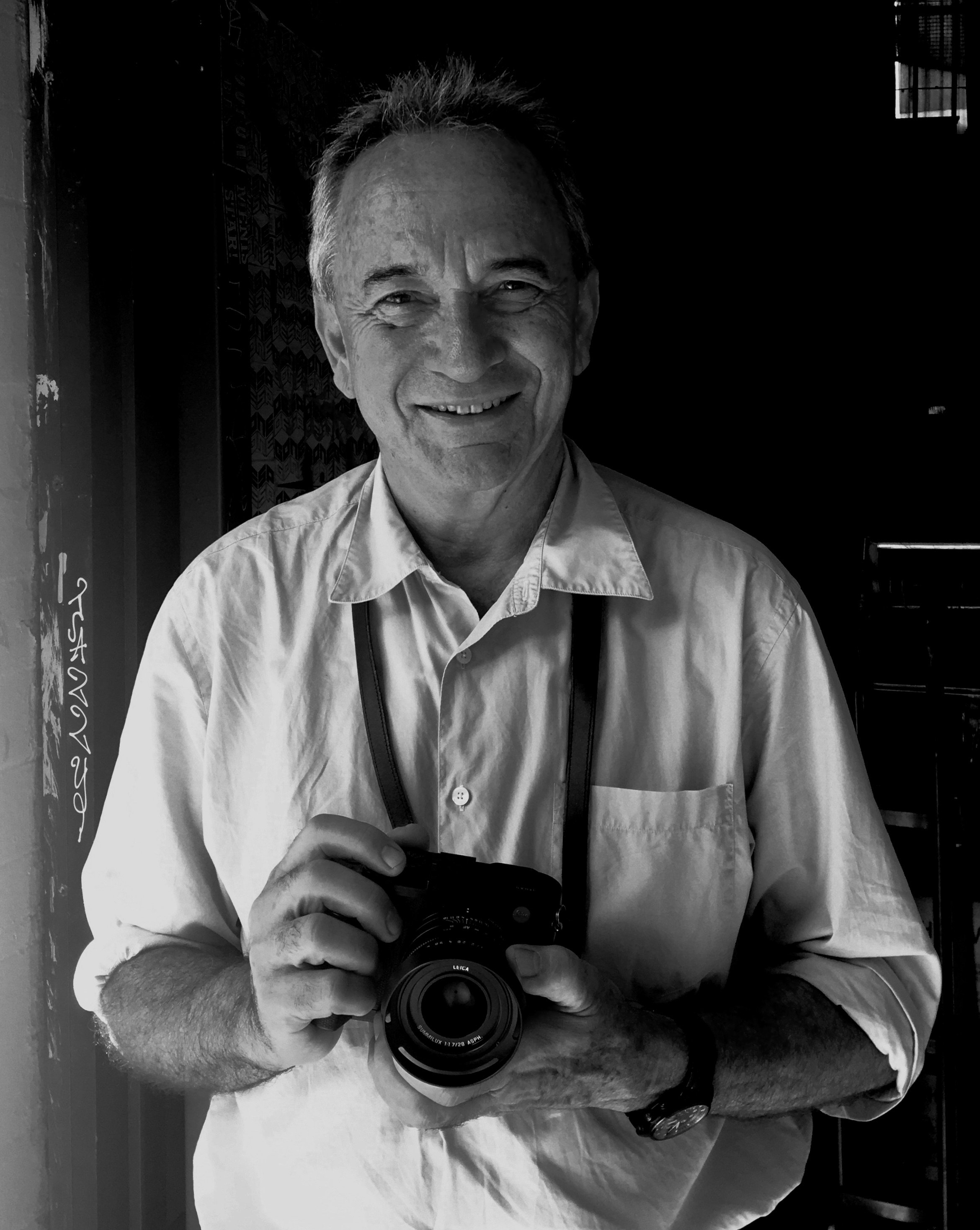

For ten years, Ilias Bourgiotis recorded life on the set with Greece’s greatest film director – until minutes before Theo Angelopoulos’ tragic death. A travelling exhibition and new book celebrate their strange, intuitive and largely silent collaboration.

Head On Interactional’s Features Editor Tony Maniaty sat down with Ilias Bourgiotis in Athens to find out more…

Piraeus, Greece / ‘The Other Sea’ © Ilias Bourgiotis

It was a moment he didn’t capture, but can never forget.

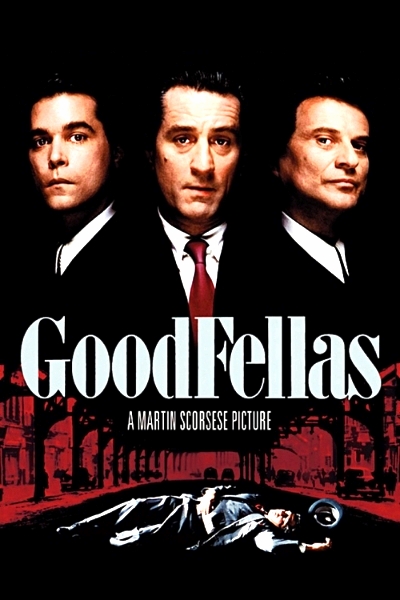

In 2012, Ilias Bourgiotis, the acclaimed Greek photographer, was standing right behind Theo Angelopoulos, the director hailed by Martin Scorsese as a master of modern cinema, in the port of Piraeus. On location, Angelopoulos had barely started shooting The Other Sea, the last film in a sweeping trilogy that included The Weeping Meadow and The Dust of Time.

Night was coming down. Just minutes earlier, Bourgiotis had taken what would be the final image of Angelopoulos alive. As he lowered his Leica, he watched the director stepping off the sidewalk – and into the path of an oncoming motorcycle. Bourgiotis witnessed the terrible impact.

A few hours later, Angelopoulos was pronounced dead.

Keratsini, Greece / ‘The Other Sea’ © Ilias Bourgiotis

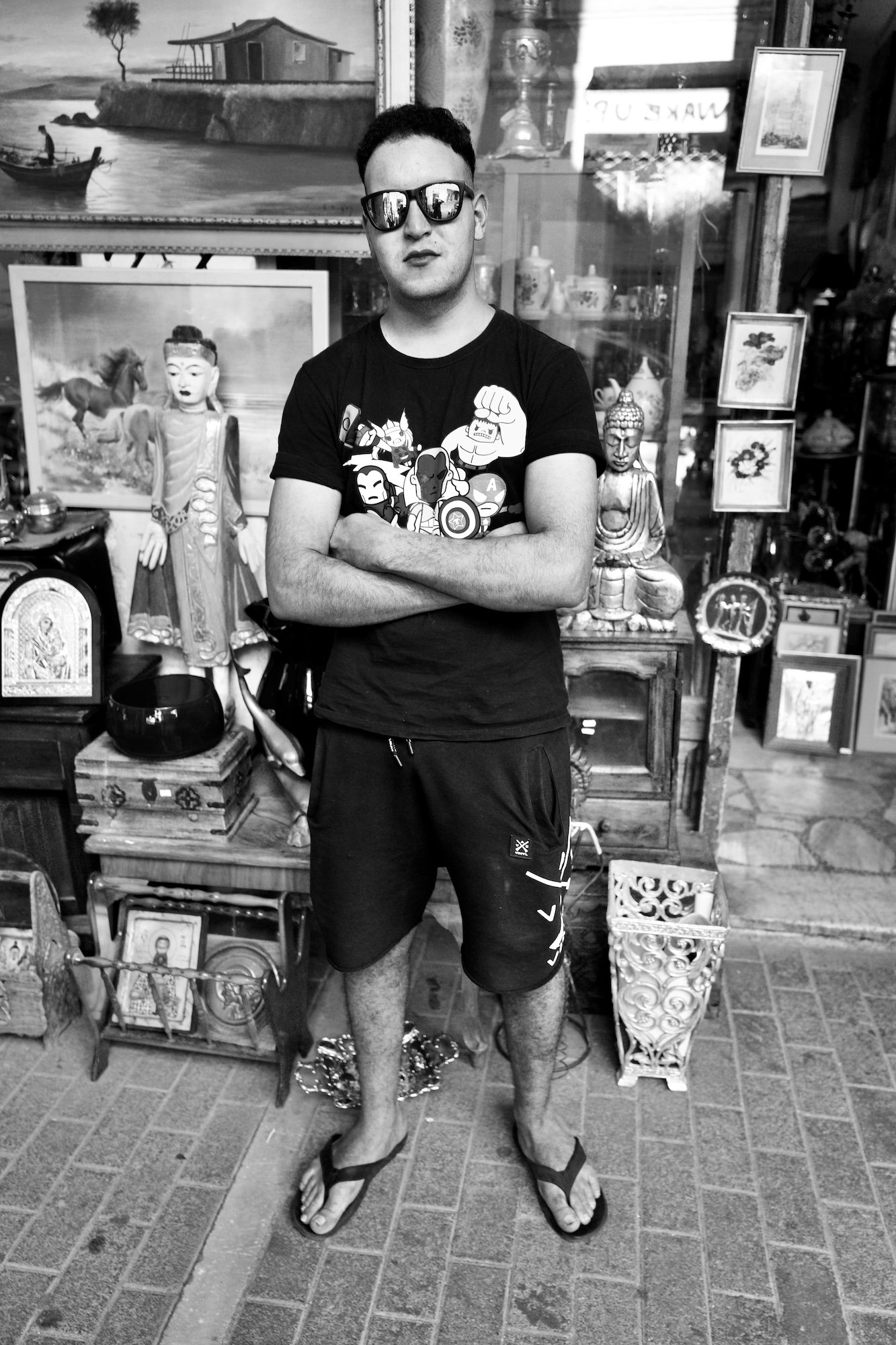

Their collaboration had begun as oddly as it ended. Bourgiotis, by 2002 well established in Greece for his photography of a rapidly changing society and of the southern Mediterranean countries, was searching for a new project. “What happened with me and Angelopoulos?” he asks reflectively, sitting with his partner and translator Allegri Voulgaraki in a noisy café.

“What attracted me initially was the philosophical and poetic nature of his films. I’d heard he was going to start shooting the first film in a trilogy, so asked for permission to photograph him at work. Then I travelled to the north of Greece, on a big lake where they were filming. It was six o’clock in the morning and everything was covered in mist, and blurry.”

Lake Kerkini, Greece / ‘The Weeping Meadow’ © Ilias Bourgiotis

“And you’d never met him before this?”

“Never. I started taking photographs of him and Angelopoulos turned around and said, ‘Who are you? What are you doing here?’ And instead of explaining anything, I handed him a copy of my book, Unseen Greece. In some ways that book has the aura of Angelopoulos’ work too, so it was my visiting card, and he saw instantly what I was about. He said nothing, absolutely nothing. And I just started shooting. That’s how our collaboration began.”

Soon after, Bourgiotis took a photo of the film’s clapper board, then the same shot without the board. “And Angelopoulos, who was curious about everything, said, ‘Why are you doing that?’ I told him one of my favourite poets was T.S. Elliot, and there’s an opening line where he says, ‘In the beginning is my end.’ Angelopoulos said, ‘That’s one of my favourite quotes too.’ And that sealed it, we were brought together by T.S. Elliot.”

Lake Kerkini, Greece / ‘The Weeping Meadow’ © Ilias Bourgiotis

Lake Kerkini, Greece / ‘The Weeping Meadow’ © Ilias Bourgiotis

What sort of man was Theo Angelopoulos?

Bourgiotis ponders a moment. “He was a slow talker. He used his hands a lot when he was explaining, always drinking coffee and smoking. He knew modern Greek history profoundly, and about the Balkans. He’d found a method of telling these complex stories, in ways that were political but also very profound.” (‘Maybe it’s sad,’ Angelopoulos declared at the 1999 Cannes Film Festival, ‘but my ancestor Aristotle said that melancholy is the source of creation.’)

The Other Sea – the director’s 14th film – was to be set around the port of Piraeus, with its constant arrivals and departures of ships, ‘like a perpetual migration, internal and external’, themes which drove his cinematic output. Critics also focus on Angelopoulos’ slow rhythms, and wide shots held for minutes while actors move like marionettes around the brooding landscape. Bourgiotis found that level of intensity matched his own approach.

Lake Kerkini, Greece / ‘The Weeping Meadow’ © Ilias Bourgiotis

“In all forms of art, easiness can be destructive. We see it now with digital production – but that’s how things happen in these times: everything is fast, and all happening at once. A more monastic behaviour is perhaps necessary so that you don’t lose the ability to grow and develop your art. What I am trying to do is photography that lasts in time. It’s not something you forget the next day, it’s not meant to be popular.”

Now, ten years after the director’s death, Bourgiotis reflects on their time together. “I ask myself, what was I really doing there? Certainly, I was not trying to record what Angelopoulos was actually doing. I wasn’t doing publicity stills. What I was doing was my interpretation of what he was doing – creating a kind of passport to allow people to enter that special film environment as I saw it.”

National Theater, Athens / ‘The Other Sea’ © Ilias Bourgiotis

And what did Angelopoulos think of Bourgiotis’ images?

“He was often travelling between films, so we never really saw each other to discuss the photos. He saw only a few. And he didn’t live to see my book, of course. Out of respect for what happened, there was no question of me selling the final photograph of him to the newspapers, to make money out of it. That image is both tragic and important to me. And to his wife – she said publicly the photo was chilling, because in it Theodoros seems to be looking at his own death…”

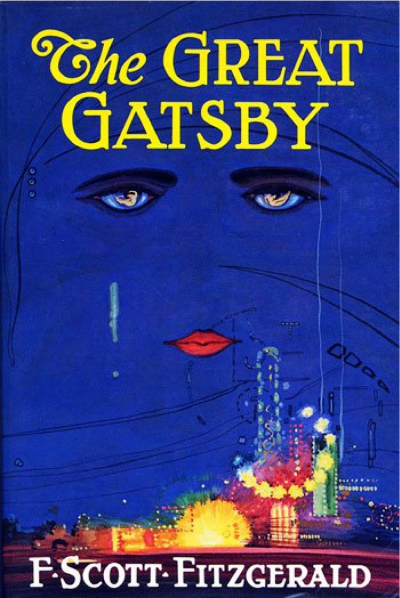

The resulting book is The Gaze of Eternity, blending the titles of two Angelopoulos films, Ulysses’ Gaze and Eternity and a Day. The photos seem immutable. “In a way, they’re like Angelopoulos’s films,” says Bourgiotis. “At an exhibition of Wim Wenders photographs in Berlin, I told Wenders that I’d taken photographs of Angelopoulos on the set. And he grabbed my arm, and said, ‘Tell me everything about Angelopoulos.’ That was the impact he had on other great filmmakers.”

“Could The Other Sea be completed, by another director?”

“A couple, including Wenders, considered it,” Bourgiotis says. “But they realised it’s not possible. Angelopoulos was unique.”

Born in Athens, Ilias Bourgiotis is a freelance photographer who work appears regularly in Greek magazines and newspapers. His photographs have featured in museums, galleries, and photography festivals in Greece as well as the United States, Italy, France, Belgium, Finland, Switzerland, Denmark, Slovakia, Croatia, and Spain. A selection of his photographs are included in the permanent collections of the Macedonian Museum of Contemporary Art and the Thessaloniki Museum of Photography. [Photo © Tony Maniaty, 2022]

This article first appeared in Head On Interactional magazine, 8 December 2022.

![“[American Psycho] is throughout numbingly boring, and for much of the time deeply and extremely disgusting. Not interesting-disgusting, but disgusting-disgusting: sickening, cheaply sensationalist, pointless except as a way of earning its author so…](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/577997d82e69cf36234d7a3d/1467862234519-P8KIUSCMHDG1KNKVFKDL/image-asset.png)

![“[Ulysses] appears to have been written by a perverted lunatic who has made a specialty of the literature of the latrine… There are whole chapters of it without any punctuation or other guide to what the writer is really getting at. Two-thirds of it…](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/577997d82e69cf36234d7a3d/1467862615565-5EVFGGHRQT1J4UPOIR27/image-asset.png)